Irish Megalithic monuments

There are four main types or groups of megalithic monument to be found in Ireland. The boundaries between these classifications sometimes blur and overlap. In the main we have firstly passage-graves ( also known as passage tombs or chambered cairns ) with perhaps 300 - 500 on the Island. Passage-graves were built by colonising farmers from Brittany who began arriving near Sligo, where an extremely early causewayed enclosure appeared at Magheraboy around 4,150 BC. Notable clusters of these monuments are often found in complexes arranged carefully in the landscape. Notable complexes are found at Carrowmore and Carrowkeel in County Sligo, along with Loughcrew and the Boyne Valley in County Meath.

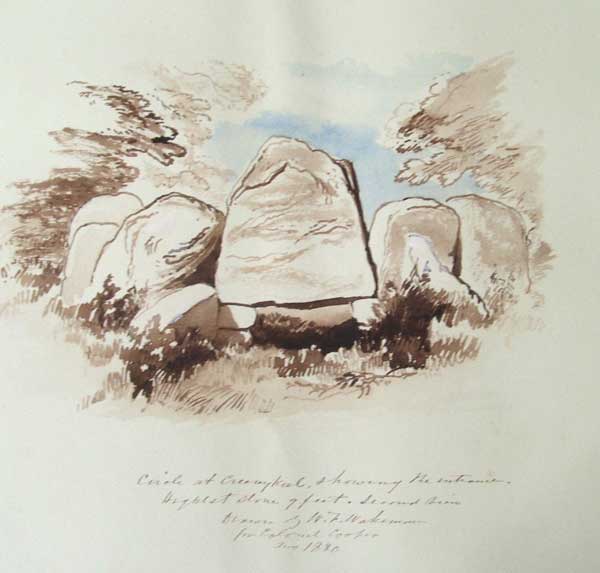

The next type of monument most commonly found are called court tombs, ( court cairns or Giant's Grave ), about 400 of which survive, usually in poor state, mostly in the northern half of the country. The largest and most impressive remains are found around Donegal Bay, with notable examples around the Ceide Fields and Rathlackan, Deerpark and Creevykeel in County Dligo, and Shawly, Malinmore and Glencolumbkille in County Donegal.

Portal dolmens ( portal tombs, Giant's Griddle's or cromleacs ), some 190 examples and wedges, again around 400 monuments. A fifth type or category are unclassified monuments of which there are at least 200. There is a sixth much smaller group, called Linkardstown cists, which are not very common.

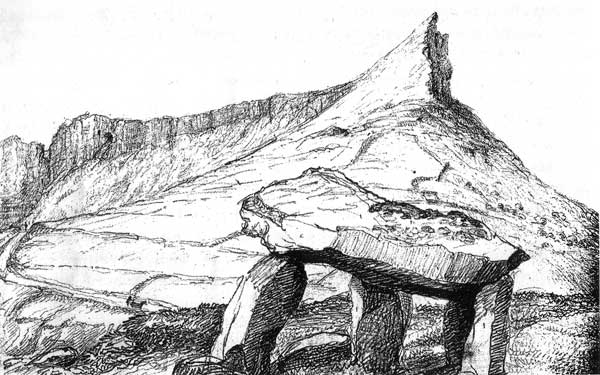

Chambered cairns are the main type of megalithic/neolithic monument featured on this website: they were the first to attract my attention, mainly due to their fabulous art and astronomical alignments. These structures are found in most European countries with large and well preserved concentrations found in France and Ireland. I was lucky, in fact I feel privilaged, to have lived at Carrowkeel in County Sligo, one of the major Irish complexes, for 10 years. Moytura, on the east shore of Lough Arrow is one of the best places to see the four types of monument. Heapstown and Shee Lugh are passage graves; the Labby Rock is one of the larger dolmens in Ireland; there are a number of wedges and an unusual court structure, as well as many tall erratic standing stones.

There are similarities and differences between the types of monuments. Courts and dolmens are thought to be the oldest types, dating to about 4,000 BC, followed by passage graves, 3,800 BC onwards and wedges on the threshold of the bronze age. There is a huge amount of variety to the 1,600 or so megaliths remaining in Ireland. Some are huge like the Boyne Valley cairns, some are tiny like the circles in Carrowmore. Many have been destroyed where they made convienient building materials or stood on good farming land. Others are so ruined that there is little left to see of the monument, but the landscape settings are often quite dramatic. Some are in great condition and easy to visit like the Labby Rock and Creevykeel in County Sligo.

Court cairns come in all shapes and sizes, and many monuments are quite ruined. There are only 12 of the great central courts, of which Creevykeel is the best example; all found in the northwest around Donegal Bay. Courts are not found in the south of the country; all but five are found in the northern portion of the island. More information on the court cairn page.

Dolmens may be markers for boundaries or territory. They are often found in valleys close to a stream, and the view does not always seem too important. Dolmens are well known for their large imposing capstones; Irish dolmens range from about 10 tons at Carrowmore to an estimated 100 tons at Brownshill in Co Carlow. Some of Ireland's largest dolmens are found in County Dublin, though many are collapsed. We could do with a national dolmen rebuilding programme in Ireland. More information on the dolmens page.