Fr O'Flanagan's stay of some fifteen months in Cliffoney was his first rural posting after many years of traveling and fundraising.

Cloonerco Bog Protest, June 1915

(from They Have Fooled You Again by Denis Carroll, 1993, pp. 37)

On the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, June 29th 1915, a holiday of obligation, the congregation at the 12.30 pm mass were requested by Fr O'Flanagan to remain after mass. He wished to say something about the local turf banks.

An evidence of the ubiquitous role of the RIC is that a Sergeant Perry also remained behind to note in detail what Fr O'Flanagan had to say. It was very direct, very simple: people were sick of promises and of the injunctions of MPs to keep quiet in the hope that when the war was over home rule would be given.

Michael O'Flanagan continued: 'I would advise every man and boy who wants a turf bank and can work a spade to go to the waste bog tomorrow and cut plenty of turf.' He would go himself and show that he could cut turf too. There was no need to be afraid. The creator had put the bog there for the use of the people. They might not be as well fortified as if they were in a German trench; nevertheless they would provide formidable opposition to anyone who might interfere with them. As in his letter to the Board, Fr O'Flanagan argued that people should not have their children shivering for want of a fire. It was agreed that people would assemble at Fr O'Flanagan's house on Wednesday 30th and march thence to the bog.

Another police spy, Barry, later deposed that a notice was pinned to a tree in the chapel grounds: 'If you want turf, start cutting at once. You will get lots of good example tomorrow. Let every man able to handle a spade be there. No admission charge to spectators.' On Wednesday, turf cutting commenced at Cloonercoo.

Ultimately, about two hundred people led by Fr O'Flanagan and Dr John Nally cut three trenches of up to twelve thousand cubic feet of turf. The turf was banked and distributed close to the RIC barracks.

Through the summer, the case simmered. Rumors of prosecution abounded. On August 18th an injunction was sought by the Congested Districts Board against Fr O'Flanagan, Dr Nally, Patrick Gilgan, Charles McGarrigle, Francis Higgins and Andrew Harrison. The injunction was granted. During the hearing, the Board agreed that it was a reasonable thing to sell turf-plots to land holders other than their own tenants. Eventually, the people championed by Fr O'Flanagan and his colleagues were allotted a part of the bog on the Hippesley-Sullivan estates without prejudice to other needy people.

Many years later, in 1976, survivors of the march to the bog spoke of the dynamic leadership given by Fr O'Flanagan in that symbolic protest of 1915.

Confrontation at Sligo and the removal of Fr O'Flanagan from Cliffoney.(from They Have Fooled You Again by Denis Carroll, 1993, pp. 37)

On October 9th 1915, a public meeting was convened at Sligo courthouse under the auspices of the Sligo Agricultural Committee and the Board of Agriculture. The object of the meeting, one of many called throughout the country, was to resolve that farmers grow more tillage. Chaired by Canon Doorley, later bishop of Elphin, the meeting was packed with official personages such as the the crown solicitor for Sligo T. H. Williams and the RIC district inspector, O'Sullivan. T. W. Russell, the vice president of the Board of Agriculture, delivered the main address while perfunctory affirmations were made by figures lay and clerical. Russell's proposal went unquestioned until Fr O'Flanagan rose to propose an amendment.

Fr O'Flanagan's address was radical and humorous, wide-ranging and well-informed. The thrust of his argument was that Russell's proposal, in itself unexceptional, was nonetheless unworthy of acceptance. The resolution should be rejected unless it was accompanied by radical provisions for land reform. Fr O'Flanagan argued that any planning for increased grain production should look to 1917 rather than the coming year. By 1917 Europe would be in greater need than ever while America would have far less grain to spare. While Arthur Balfour was confident that England could avert the German submarine threat, O'Flanagan reminded his hearers that Irish people had little reason to venerate Balfour either as an historian or as a prophet. Should food shortage occur, should Ireland's black '47 be transferred to England of 1917, neither a conscript army nor unlimited supply of high explosives, the accumulated fruit of the war effort, would be of avail. In regard to food production, 'a few tuppence halfpenny meetings, a few jack-in-the-box speeches and a placard in front of every police barrack, will not dig out of the soil the roots of a grass that has been growing deeper into the soil for seventy years."

To be serious about a tillage program, two million acres of Irish land, instead of a mere seventy thousand to eighty thousand acres, should be under tillage. In effect, O'Flanagan was proposing an agrarian revolution whereby the ranches which occupied Ireland, in its central plain from Sligo to Dublin, would be divided and given to people ready to till those hundreds of thousands of acres. For that to happen there was need for 'an agricultural Lloyd George...... a tillage Lord Kitchener.' On the lips of one who opposed Lloyd George and Kitchener, this was a surprising utterance. Yet it simply meant that the energy devoted to war should be matched by a corresponding vigor in land reform. Ample powers and sufficient money were an essential prerequisite. 'A hundred millions given a tillage minister will grow into a golden harvest.' Instead of the detestable custom of abusing the farmers' sons because they would not go into the British army, 'invite them back upon the rich plains from which their fathers were driven.' From the bogs and mountain sides of Ireland's barren fringes, O'Flanagan would have them come. Were that to happen it would be evidence that 'the old sinner has repented, intends to disgorge his ill gotten gains, even though the repentance may have come under the terror of the skeleton hand of death.'

In O'Flanagan's view, Russell's plea for an increase in grain production meant no more than a small respite in the case of shortage. 'Instead of commencing to starve on the 5th of January 1917, we shall be able to keep body and soul together for fifteen days more.' Clearly O'Flanagan did not expect his proposal that a million a day be devoted to tillage in Ireland and England would pass into effect. And so he recommended people to ensure that famine was kept from their own doors. They should ignore the Board of Agriculture and adopt their own remedy..... They should 'Stick to the oats.' This call has ever since been associated with the curate of Cliffoney. O'Flanagan's speech ended with a rousing call: 'The famine of 1847 would never have been written across the pages of history if the men of that day were men enough to risk death rather than part with their oat crop. Let each farmer keep at least as much oats on hand to carry himself and his family through in case of necessity till next years harvest.'

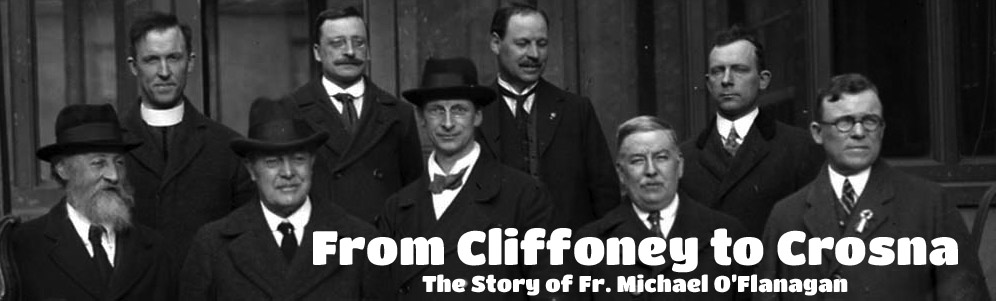

The Rev. Michael O'Flanagan who has gone to America as Ireland's envoy, October 1921.

The report of the meeting discloses the hectoring customary in officialdom under pressure. Russell called upon the meeting to ignore the O'Flanagan amendment even if they were to vote down his own resolution. O'Flanagan's request, he said, was like asking for the moon. 'You are carried off your heads,' he averred, 'Vote down the Board's resolution and put yourself out of step with the rest of the country.' Replying to Russell's jibe that the opponents of his motion were play-acting, Michael O'Flanagan declared that Russell and his like were more experienced in the game of play-acting than the people at the meeting. Canon Doorley put the resolution rather than the amendment to the meeting. It was passed.

In a matter of days Fr O'Flanagan was changed from his parish at Cliffoney. It was a chilling reminder, not the first and by no means the last, of the collusion between higher clergy and higher officialdom. It may also be a further evidence of the unease in both Church and State before the words of a radical social critic.

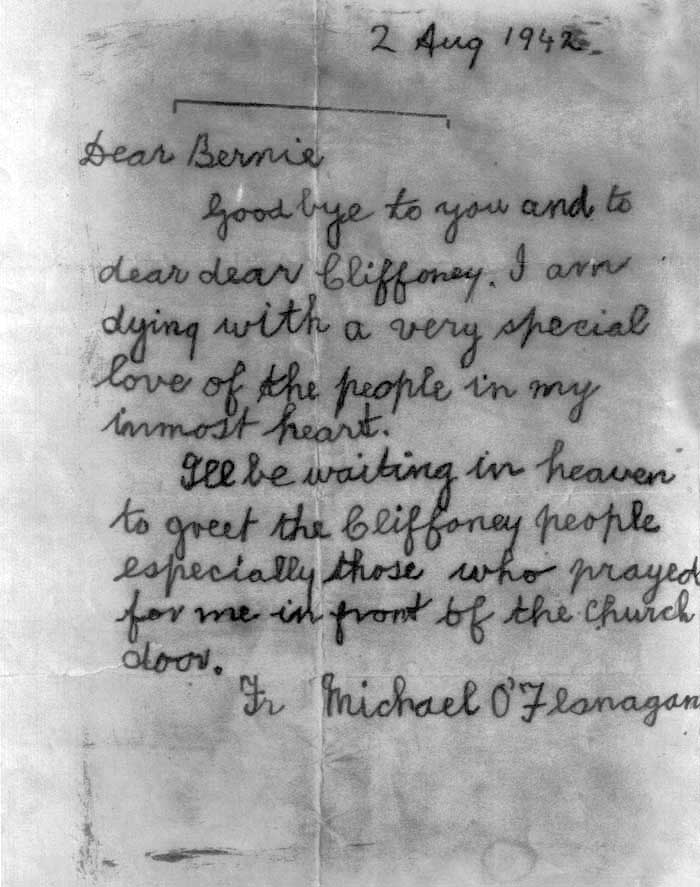

However, the people of Cliffoney did not share their bishop's view. Having fruitlessly approached Dr Coyne on several occasions, they barred the church against Fr O'Flanagan's unfortunate successor, Fr McHugh. The rosary was regularly said outside the locked church. Prayers for Fr O'Flanagan were recited at the foot of a cross in the church grounds.

A few weeks after Fr O'Flanagan's precipitous removal, a resident of Cloonkeen, Cliffoney repeatedly asked the bishop that 'you will send us back our poor, dear Fr O'Flanagan who was an ornament to the Roman Catholic church of Cliffoney and who, during his short stay with us, has discharged his duties in a manner that no other priest has done in my memory'.

Dr Coyne's firmness outpaced his courtesy to the people of Cliffoney and Grange. He remained obdurate to all protests, refusing either to alter of explain his action in regard to Fr O'Flanagan. The church remained closed until Christmas Day, 1915.

The Liberator (Tralee) Tuesday, November 09, 1915; Page: 6

CO. SLIGO VILLAGE SCENE

PROTEST AGAINST THE CURATE'S TRANSFER -

Parishioners Dispute with R.C. Bishop

Church Locked and Barricaded.

An extraordinary situation exists in the little village of Cliffoney, Co. Sligo. The inhabitants are entirely Roman Catholic yet for the past three weeks none of them have attended devotions in the local church, in consequence of a disagreement with the Bishop of the Diocese. The church itself has been barricaded. The doors have been nailed up, and logs of wood piled against them. Sentries have kept guard night and day. Each Sunday morning the parishioners have, assembled outside the church, and kneeling in front of the door, have recited the Rosary. The reason for this state of affairs is than the Bishop of tne Diocese, Most Rev. Dr. Cloyne, three weeks ago removed the officiating curate, Rev. Ml. O'Flanagan. The people strongly resented this believing it to be in consequence of certain speeches delivered by Father O'Flanagan.

Cliffoney is situated in the middle of a large bog, and Father O'Flanagan has been curate there since 1914, when he returned from America, where he had been in charge of the Gaelic League financial mission. The people of the district state that they and their forefathers have cut turf in the adjacent bogs since time immemorial. The Congested Districts Board bought the estate and wished to hand over the turbary rights to other purchasers. Turf is the only fuel used in the district, and the people refused to recognise the right of the C.D.B. to dispose of it. One bank of turf had been usually set aside for the curate. In a speech Father O'Flanagan recommended the people to cut the turf as they had always done. This was done, and there has already been litigation regarding the matter. While the local farmers were "saving" Father O'Flanagan's turf efforts were made by the police to stop it. The authorities, however, were defied.

The next incident of importance seems, to have been a speech made by Father O'Flangan at Sligo at a meeting held under the auspices of the Department of Agriculture. Mr. T. W. Russell having spoken of the necessity for incasing tillage, Father O'Flanagan said that Mr. Russell "did not understand what he was speaking about!'" The practical consideration was to provide against scarcity in the summer of 1917. The following are a few extracts typical of the speech: —

England's munitions campaign does not consist of a man with a tin whisrle playing "Pop goes the weasel" in front of powder factories. A few twopence half-penny meetings, a few jack-in-thebox speeches, and a placard in front of every police barrack will not dig out of Ireland the roots of a grass that has been growing deeper into the soil for seventy years. Is there anybody sanguine enough to hope that, the result will be 100,000 acres of wheat instead of the 70,000 of the past years? What is the meaning of such a result in terms of the Irish food supply? It means that instead of having homegrown bread for 35 days we shall have enough for 50 days. So that instead of commencing to starve on the 5th of February, 1917, we shall be able to keep body and soul together for fifteen days longer. And now the Congested Districts Board informs us that a Treasury that is spending £5,000,000 a day upon the war must economise by withdrawing the beggarly mite that has been doled out to the Board. It is then going too far to ask whether this, is a real tillage movement or only a sham tillage movement? But though the Government may have no real tillage policy, the Irish people ought to see to it that the danger of famine is kept away from their doors.

And when it comes to England and Ireland starving, Ireland will have to starve first. Even though a famine appears in Ireland, England will go on with the war and allow Ireland to starve. When the famine reaches England, England will make peace. And if, as a result, she is reduced to the position of second or third of the great Powers of Europe, she will at least have the satisfaction of having advanced another step on the ghastly road she has so long followed in search of a solution of the Irish difficulty.

There is one remedy in our own hands. Stick to the oats, we have only enough wheat to give us bread for five weeks of the year, we have oats to give us better bread for the whole year round. The famine of 1847 would never have been written across the pages of Irish history if the men of that day were men enough to risk death rather than part with their oat crop. Let each farmer keep at least enough oats on hand to carry himself and his family through in case of necessity till next year's harvest. And if any Government dares to commandeer your oats, remember that it is better to die like men fighting for your rights than to starve like our poor misguided grandfathers seventy years ago.

That speech was delivered on a Saturday. On the following Tuesday Fr. O'Flanagan received from the Bishop a notification of his transfer to Crossna, near Boyle. The principal parishioners immediately procured the key of the chapel and locked it. Some time later the parish priest (Rev. M. Shannon) and the new curate obtained an entrance. It is stated that they were ordered out, and the church was then barricaded, and guards placed.

Two deputations have waited upon the Bishop, but without result. On the first occasion 300 men and women travelled to Sligo on cars, bicycles, and on foot. They marched through the principal streets of the town and sent a deputation to the Episcopal Palace. At that time, the Bishop was not at home, but the deputation interviewed another dignitary, who strongly remonstrated with them. The Bishop refused to receive a deputation which was sent later.

The situation consequently remains unchanged.—

===================================

The Fr O'Flanagan hall in Cliffoney after it was burned by the Auxiliaries in reprisal for the Moneygold ambush in 1920. A little on the history of Cliffoney Hall from Bernard Meehan and Patrick McCannon:

On Sunday morning, 5th May, 1916, with thirteen or fourteen members of the Cliffoney Company I was arrested by British Forces. We were conveyed, to Sligo Prison, thence to the, then Richmond Barracks, Dublin, and from there to Wandsworth Prison, England, where I was interned until July, 1916. After my release from internment, the Volunteer Force was again organized in the Cliffoney area.

With Willie Gilmartin and Andy Conway I took an active part in the reorganization.

There was no hall in or around Cliffoney where we could meet but there was a vacant school-house, the property of Colonel Ashley. This we decided to take over and use as a hall.

A party of Volunteers marched up on a Sunday evening and entered the school. In a very short time the R.I.C. who were stationed just across the road, came into the school to investigate. We were prepared for any questions they might ask. We had already provided ourselves with Irish Trade Union membership cards and told the R.I.C. that we were holding a Union meeting. Apparently they were satisfied with our story as they did not molest us there for some time.

We cleaned up the place and it was used as a Sinn Féin hall for some time afterwards. It was burned in October, 1920 by British Forces.

And from Patrick McCannon of Cliffoney:

1917 arrived with little hope of the Great War abating or reaching a climax. The Republican leaders in Ireland who had escaped and survived the slaughter after Easter Week were once again in active counsel but had to move cautiously as they were continuously watched and shadowed.

At that time there was no parish hall in Cliffoney but there was a vacant schoolhouse (belonging to the landlord, Colonel Ashley) which some time previously had been closed. The company leaders had a hungry eye upon it. others, too, had it wider observation as it was ideally situated. As people were returning from Devotions on a certain Sunday, as previously arranged a section of Volunteers marched to the door of the building, forced it open and took possession, to the bewilderment of the R.I.C. as the barracks was almost directly opposite.

As the Irish Volunteers was proclaimed an illegal organization at that time, the forces of occupation were once again at work contemplating the closing of the building, which was considered a menace. However, the R.I.C. were outwitted. On entering the occupied building, in force, and on questioning those present they were coolly informed that the occupants were not members of any illegal organization but belonged to the Irish Trades Union and produced membership cards. Afterwards: the building was renovated, gaily decorated and painted in green, white and gold and made a Sinn Féin hall. When opportunity presented it was an instruction and training hall for the Volunteers. It was burned In October, 1920, by British forces.