The Manchester Martyrs

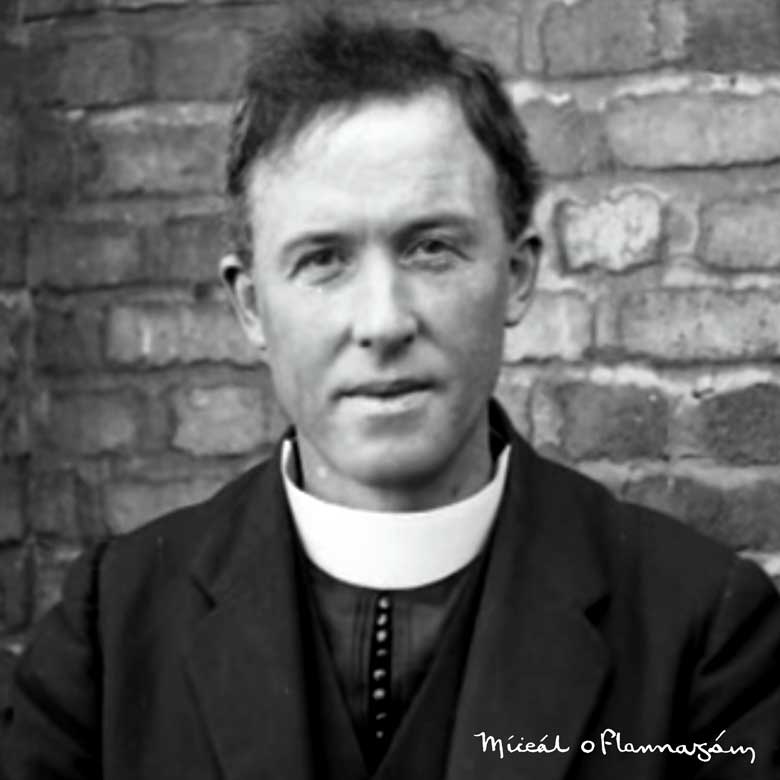

Speech by Fr. Michael O'Flanagan, Boston, 1911.

Forty-four years ago today three Irishmen were publicly hanged in the city of Manchester. The act for which they gave up their lives was universally regarded in England as a crime of the deepest dye. In Ireland that same act was looked upon as a deed of the noblest heroism. England dumped their bodies into a pit in the back yard of an English jail, and has left them there ever since. Ireland carried their empty coffin in a hundred magnificent funerals and draped her altars amid scenes of universal mourning unparalleled in her entire history. A song composed about their death has been Ireland's national anthem ever since.

Allen, Larkin and O'Brien were not executed for the crime of which they were convicted in the law courts. They were not hanged for the murder of Sergeant Brett. The same judge and jury that condemned them to death condemned Maguire also, and yet Maguire was set free because in spite of the evidence and in spite of the judge and jury it was manifest that he was innocent; not for killing Sergeant Brett but for setting free the leaders of the Fenian movement were these men hanged. The leaders of the Fenian movement whom they set free were arrested without proper warrant and detained in violation of the English law.

The policemen who guarded the van and the magistrate who ordered them conveyed from the Court House to the prison were the real law breakers. The Irish patriots who smashed the van were, according to the opinion of the best lawyers of today, perfectly entitled to do what they did. To glut their blind vengeance against these Irish patriots trampled upon her own laws and upon all the safeguards that centuries had erected for the protection of human life.

The great significance of the incident lies not in the fact that three innocent men were murdered, not that three other notable Irishmen had yielded up their lives for the love of their country, for they are only three out of many thousands who have done the same for centuries and who have done so since. But it lies in the fact that it brought home to the minds of the Irish people with unusual clearness the difference that lies between the nationality of the Irishman and of the Englishman.

We are here tonight to commemorate the death of these men, but ours is not a mere empty commemoration. We are here to help to preserve and to perpetuate the difference of nationality which led to their death. All through the centuries the aim of England has been to break down the barriers that separated her from Ireland, to extinguish the national customs and characteristics that formed the separate civilization of Ireland, and to root out the language which enshrines the distcint mind of the country.

But our motto is "Up with the barriers"! England proscribed our language and rooted out our educational system. She burned our schools and drowned our books, and eighty years ago she established in Ireland a foreign system of schools that would build up her civilization in place of the native civilization that she had destroyed. The Gaelic League has forced open the doors of more than 3,000 of these schools to the teaching of the Irish language, and thus the strongest weapon devised for our destruction is being turned into an instrument for our national restoration.

For generations the Irish people have struggled for the right to rule themselves. It is a sacred and inalienable right, but it is inalienable only so long as there is an Ireland with national characteristics different from England to demand it. It is only with the advent of the Gaelic League that it has dawned upon the Irish people that their national characteristics, which forms the basis of their life could be lost, and then we should have ;lost, not merely the right to self-government, but even the desire for it. What would it avail to save the body of Ireland and lose the soul? An Ireland that has lost its national language and with it the other characteristics of its separate civilization, would never be more than an animated "scare-crow".

Once upon a time a minister of a certain church made a close study of the history of early Christianity and as a result he came to imitate closely the ritual and ceremonies of the Catholic Church, and as if to complete matters he hired an old Irish Catholic woman for a housekeeper. He took her into the sacristy one day in order to show her that there was no difference between his church and the one she had been accustomed to. He pulled out his drawers and showed her the chasuble, manciple and stole and alb, the holy water fonts, the candlesticks and the tabernacle, and then he looked at her for a sign of approval. She examined all these things carefully and then turned to him and said simply: "Ye have everything but God"!

Suppose that we in Ireland had succeeded in gaining self-government and that we made our own laws and carried on our own trade and commerce, and suppose we even flew our own flag in the Irish style over a Green-coat army. But, suppose at the same time that we had lost our national language and with it all the characteristics of our separate civilization, and suppose we could call forth from the grave the spirits of one of the great Irishmen of the past—of Brian Boru or Hugh O'Neill, or one of the four masters, and that we should show him all that we had accomplished—what would he say to us?

He would give us an answer very much like what the old Irish woman gave the minister—that we had everything but Ireland. For when you change the language of a nation you change the very thoughts that occupy the minds of the people of a nation; you change their ideals, their aspirations and their characteristics, and you substitute for them the characteristics of the nation whose language they copy. An Irish-speaking grandfather when he meets his friend upon the road will hail him with a prayer "Go mbeannuigh Dia dhuit", the blessing of God on you. And his English-speaking grandson when he meets his friend upon the road will drop the prayer and say "Hallo, how is Pat?"

The Irish-speaking grandmother when she hears bad news will say "Welcome be the will of God" and her English-speaking granddaughter when she hears bad news will say "Well, that's too bad; I'm so sorry" and if even these simple expressions of everyday life cannot live on for two generations of English speech—how can you expect that the deep thoughts of the poets and philosophers and saints of Ireland will live on after the language is dead? If even the simplest notes of the scale fail to come true from this new instrument how are we going to draw forth from it the million subtle harmonies that have been singing in the soul of Ireland throughout all her heroic past?

Round an Irish-speaking fireside you will hear told the story of Fionn and the Fianna, of St. Patrick and St. Columbkille, of Murrogh of the two swords and of Cahalmor of the wine-red hand, and round an English-speaking fireside of the first generation of English speakers you will possibly hear a faint echo of the same traditions. But round an English-speaking fireside of the second or third generation of English speakers you will hear nothing except the ordinary gossip of the cosmopolitan world, about the Chinese rebellion, or the attack of the suffragettes upon the House of Commons, and just as the local traditions of the people disappear with their language so also it is with their music and dancing.

One old Irish-speaking piper from Galway can play more Irish airs than all the piano strummers from Rathmines to Ballinasloe, whereas, the young men and women of the English-speaking districts have lost not merely the graceful dances of the Gaeltacht, but they have lost the art of dancing altogether dances of their ancestors, but the kind of monkey-work you will see exemplified in this hall as soon as the Gaelic portion of this program is through. Tonight we have the result of the first effort which the Gaelic League has made to extend the Feis to America.

When the Feis commenced in Ireland ten or twelve years ago it consisted of an examination in Irish of the school children at which prizes were given in order to encourage them to devote more than average attention to the national language. After a time prizes were given for singing and dancing and then the old people were invited to come in and compete in such things as story-telling, and recitation of poetry. After a few years the Feis was still further extended so as to include prizes for drawings and art needlework, and at the present time prizes are given for all products of local industry.

In this way the Gaelic League has given a great stimulus to industrial activity, and already the movement is felt in the domain of Irish trade. At the present time the trade of Ireland is larger in proportion to population than that of any other country in Europe with the exception of Belgium and Holland. The combined exports and imports last year amounted to $620,000,000. The trade of Ireland in proportion to population is today not merely much greater than the trade of Great Britain, but it has increased during the past half decade twice as rapidly.

One of the most effective agencies in increasing the sale of Irish manufactured goods in America has been the exhibition of Irish crafts that has been conducted in American stores during the past four years, and which is now in progress and will remain until Christmas at Henry Seigel's. This exhibition from the merchandising point of view is not very big or imposing, but from the advertising point of view it has been invaluable. For example it visited the city of St. Louis twice in 1906 and 1909 with the result that the sale of Irish goods in St. Louis went up during those two years from $20,000 to $315,000, and to show to you that this was the result of the exhibition, the greater part of the $315,000 was consigned to the store in which the exhibition was held.

If the people in this hall only realized the enormous advantage to Ireland of this exhibition everybody here would not merely visit it often between now and Christmas, but would canvas all their Irish and non-Irish friends to visit it also. We haven't got as many things as we should like to have, but the things we have got are all of the right kind and as soon as the public of Boston threaten to buy us out we shall cable to Ireland for more. We have got a great many articles specially intended and appropriate for Christmas presents, and if you buy your Christmas presents from us you will not run much risk of being suspected of giving him back one of the things he gave you last year

Some people have said to us that it would be wiser if we dropped the Irish language and concentrated all our energy upon the industrial movement. It reminds me of the suggestion made once to a train conductor to drop the engine in order to lighten the train. It is the language movement that has supplied us with the enthusiasm that has brought about the industrial movement, for with all its influence upon the practical questions of life in Ireland the main inspiration of the Gaelic League is a sentiment. I do not think, however that it will be necessary for me before an audience living in America, to make any general plea for true and noble sentiment in the life of the world.

Coming across the Atlantic a year ago on one of the great Irish-built steamers of the White Star line I was in the company of a party of about 300 Americans who were returning from a short vacation in Europe, and the day before they landed I saw them line the sides of the Baltic peering out anxiously for the first glimpse of American soil, and have I not felt the thrill that passed along their line—as the low sand-hills of Long Island stole by.