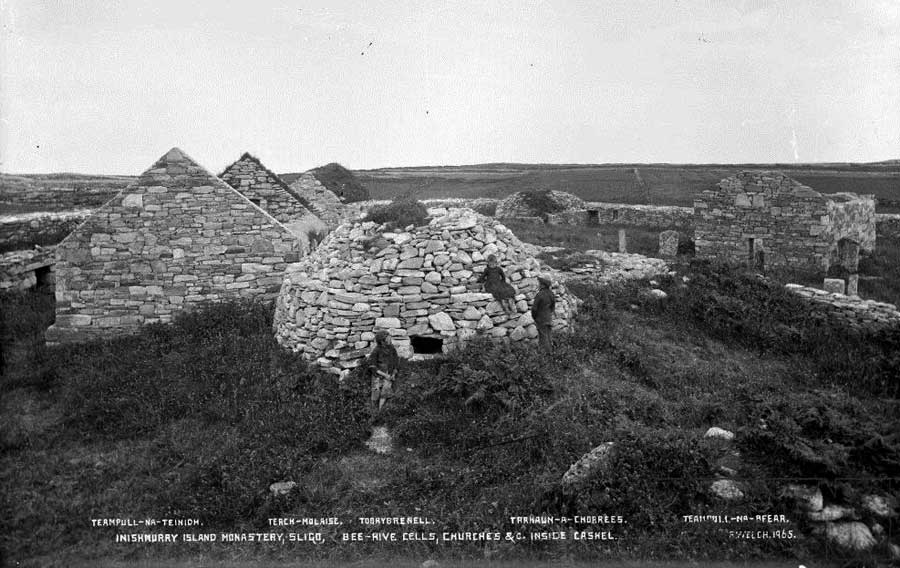

Inishmurray monastic settlement

The monastery on Inishmurray is said to have been founded around 520 AD by the mysterious Saint Molaise, a figure also associated with Rossinver and Devenish Island in Lough Erne. The Annals relate that the monks inhabited the island from the sixth to the twelth century, when they moved to the mainland at Screen and Aughris in west Sligo.

The Island has a long, many storied history that could fill several volumes. Chapters would cover the Monastic buildings, Sts Molaise and Columbkille, the multitude of engraved cross slabs and the celebrated Cursing stones, the Islanders and landowners; a special chapter would deal with industry on the Island, in particular the manifacture of fine spirits and the adventures, alarums and raids that go with such business. Fishing, Island life, folklore, costoms, and much more might come close to telling the story of this wonderful enchanting Island. I think the best way to introduce the Island and its people is to share this short story from 1933:

Inishmurray Island

To many Irish ears the name Inishmurray may sound strange. It is a small rocky island lying out in the Atlantic about 10 miles off the coast of Sligo. I venture to assert that of all the islands of Ireland it is the most destitute of tourists. It will never be overrun with them, for the Island is almost inaccessible; and granting that there were suitable boating facilities the Island would still remain immune. The reason is simple. There is no accommodation. There are eleven houses on it, all thatched and clean, and their inhabitants - more's the pity - speak English. There are some cows, a few donkeys, one jennet, some fields of potatoes, barley, and grass, and a host of coloured hens and quacking ducks. There are no shops, no rats, no post office, no wireless, no regular church, no residing priest, but it can boast two graveyards and a number of interesting ruins. Such, then, is Inishmurray.

During the summer I saw its outline on a map. It seemed to be lonely lying in the Atlantic without even a brother island in sight. It attracted me, and one evening, with a pack on my back, I came into a little village in County Sligo. I entered a pub, and I said to the barman: 'Could you tell me how I'd get to Inishmurray Island?'

'Well,' said he, 'there's an Islander here and he may be going out this evening...... Heigh, Dan!' he shouted to a small red-faced man who leaned on a far counter, 'here's a gentleman would like to go to the Island.'

The Islander, dressed in a blue jersey and grey trousers, approached, smoking a clay pipe. He looked at me with sad expressionless eyes, but he never spoke. Instead, he ordered two bottles of beer, put them into his pocket, shouldered a sack half full of sugar, and went out. I stood amazed, but the barman told me to follow him, which I did. I kept behind at a respectable distance, and occasionally made noises with my stick on the road, but the Islander never looked behind. We walked like this for about a mile, then we left the road, proceeded along the side of a field, and soon we came to the sea. Here there was nothing to be seen except a boat anchored by a rope to a big stone that lay on the shore. A man moved in the boat when he saw us coming, and jumped ashore. It was then I was noticed. Dan left down the sack, straightened his back, and, looking at me, he laughed and said: 'Sure it's coddin' I thought you were; you're as welcome to the Island as me father or me mother. Step in now, and watch your feet on the lobster pots.' The two men lifted their oars, took off their caps, and crossed themselves in prayer.

A head wind was blowing, and I offered to help at the rowing. With the strong outgoing tide, and with three oars, the boat made headway; so fast were we travelling that Dan turned to his companion and said: 'It's well we brought him. Sure it's the spiritual itself weather we have in the boat.' Whether the compliment was passed to induce me to further effort I do not know, but I was glad when Dan ordered Johnnie 'to give her the cloth.' As the boat sailed along in the gathering darkness Dan talked about politics, business done in Sligo, and the condition of the fishing industry.

It grew dark and cold and late. The two bottles of beer were produced, pipes were lighted, and the boat sailed on, to many friendly exhortations from the skipper. I looked at my watch, and it was long after midnight. A bright relic of the departing day still glimmered in the west, and in front of this the island showed up like a black, lean rat. The mainland was shrouded in darkness, and only a few fitful gleams of light suggested life.

Nearer and nearer we came, but no light shone from the Island. It looked as desolate and forsaken as an old ruin. Johnnie moved in the bow, and standing up he shattered the silence with three fierce whistles. The barking dogs reached our ears, and then a number of lights jumped to life - the Island was awake.

The boat moved closer, and a few lights from cigarette ends burned holes in the darkness. The sails were lowered, and the boat was coaxed up onto the slippery rocks of the Island, where her nose was held by a number of men and boys. There was no pier, and the boat was hauled up on the rocks.

Dan lifted his bag of sugar on his back, and cautiously I followed him up a boulder-strewn path. We halted inside a house where an oil-lamp embraced up in a soft, warm glow. A pile of turf blazed on the hearth. Two girls prepared a table silently, and a red lamp burned before a picture of the Sacred Heart. I sat on a chair and made myself at home; for it was impossible to feel backward or strange in such an atmosphere of unostentatious kindliness.

Awakening the next morning, I was surprised to see such a small world around me. The Island is not very high, but it is as flat as the proverbial pancake. It is about half-a-mile or less in width, and as for the length, a donkey braying on one end could be seen and heard at the other. How the people live is known only to themselves. There seems to be more houses than arable fields; fully three-fourths of the Island is covered with small grey round stones, grey rocks,, and a small piece of apologetic-looking bogland. Facing the mainland there is a small strip of cultivated land fronted by white-washed houses. The inhabitants pay no rates, no taxes - how could they? - and yet they have a King, who is treated and obeyed with greater respect than his contemporaries in richer lands. No Communists mar his peace!