The Carrowmore Megalithic Complex

Carrowmore is more easily accessible than Carnac; the inns of Sligo are better than those of Auray; the remains are within three miles of the town; and the scenery near Sligo is far more beautiful than that of the Morbihan; yet hundreds of our countrymen rush annually to the French megaliths, and bring home sketch-books full of views and measurements; but no one thinks of the Irish monuments.

The Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries - their Age and Uses by James Fergusson, 1872.

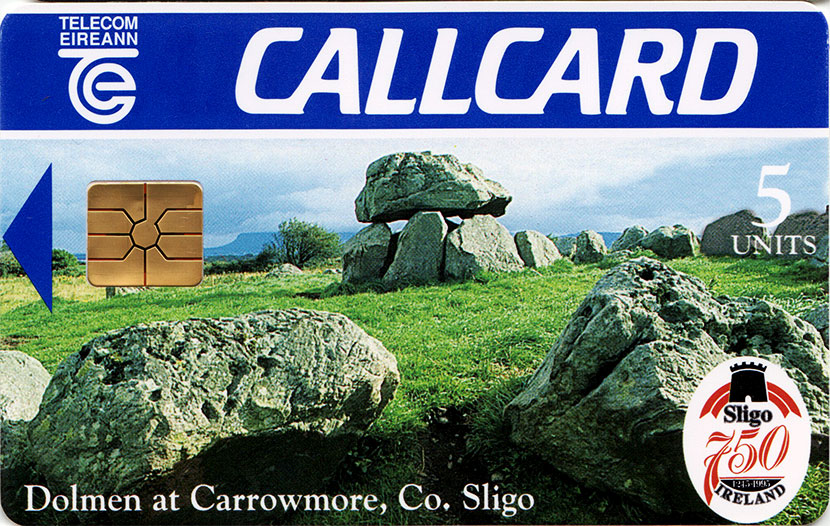

County Sligo is home to the largest and oldest collection of neolithic stone circles and dolmens found in Ireland. The monuments, an early form of passage-grave, are located at Carrowmore, a townland within an extensive landscape of prehistoric burial and ceremonial monuments at the heart of the Cuil Iorra peninsula, four kilometers southwest of Sligo town. Despite notices on Google which say Carrowmore is permenantly closed, the site is open each day from 10.00 am, with last admission at 5.00 pm, until Monday 2nd September, when the visitor centre will close for renovations.

The Carrowmore complex is arranged around the edges of a subtle plateau at the centre of the peninsula, a parcel of undulating land with fixed boundaries, surrounded by water on all sides. Ballisodare Bay, location of the First Battle of Moytura lies to the south, the wide Atlantic ocean lies to the west; and the enclosed body of water called Sligo Bay is to the north. Lough Gill, the Lake of Brightness lies to the east beyond Carns Hill, connected to the sea by the short shelly Sligo river, the Garavogue.

This almost every peak and summit in this area is capped with a neolithic monument, a later, cairn-covered form of the simpler passage-graves found at Carrowmore. According to folklore, the monuments were believed to have been built by a cailleach or hag named Garavogue who, according to local tradition, lives in her house in the Ballygawley mountains. The stunning cairn-topped mountain of Knocknarea rises abruptly four kilometers to the west of Carrowmore, while the smaller, but equally important Carns Hill is four kilometers to the east. There are more neolithic monuments on the summits of the Ox Mountains to the south.

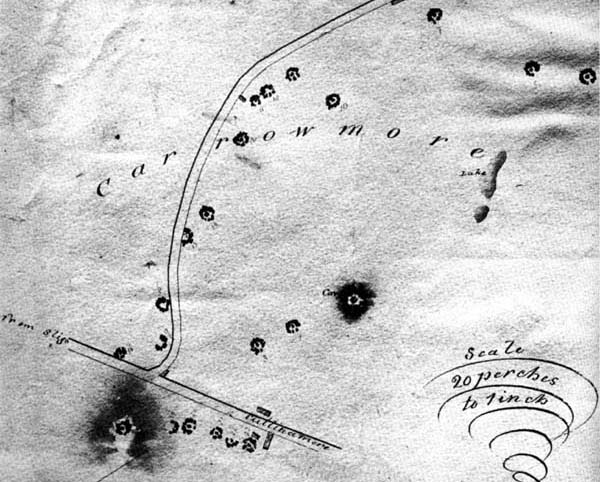

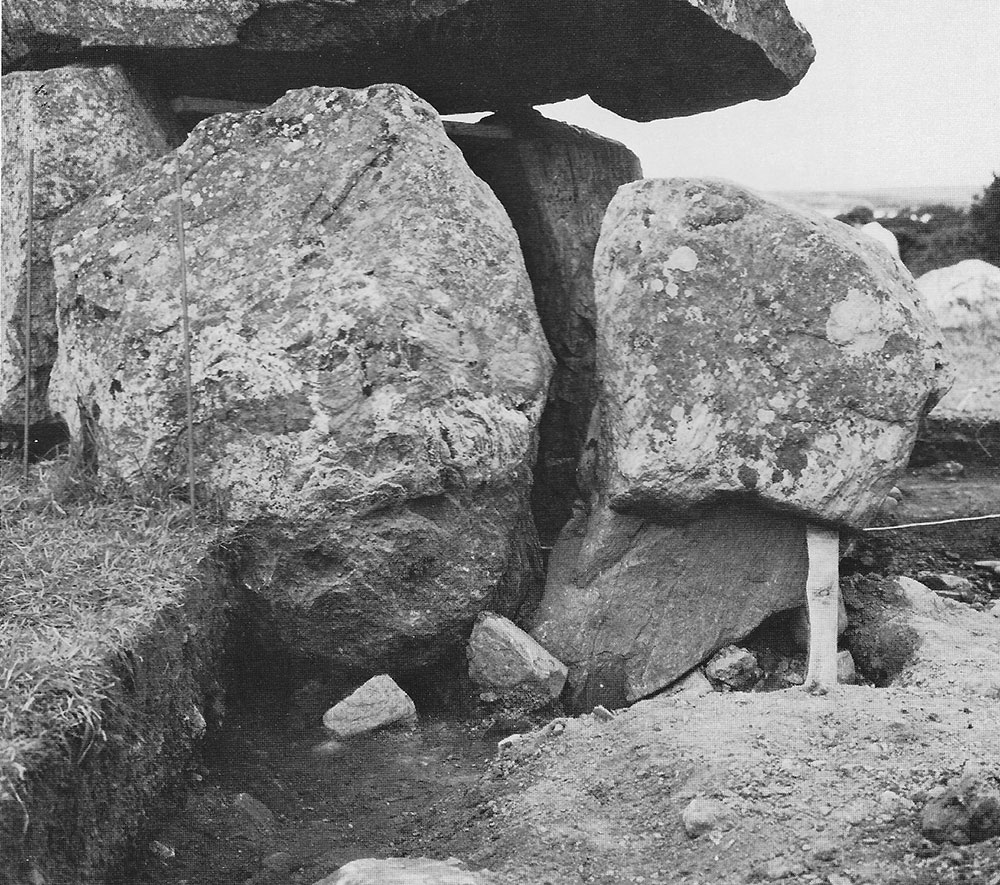

Thirty monuments remain at Carrowmore today, in varying states of preservation and completion, the most perfect being the Kissing Stone. The antiquarian George Petrie noted sixty-five monuments during his visit for the Ordnance Survey in 1837, but today the number is thought to be considerably lower at a probable maximum of not more than forty circles. A number of these sites were badly damaged in the early years of the nineteenth century by land clearance and gravel quarrying.

This website provides a virtual tour of the monuments at Carrowmore, with a page for each monument and its history of research. New information from ancient DNA suggests that the monuments were built and used by people who came by sea from Brittany in north-western France slightly over 6,000 years ago.

These voyagers brought the first cattle and sheep to Ireland, and existed by herding their flocks through the forested landscape. They also re-introduced the red deer to Ireland, the native species of Irish elk having become extinct after the last ice age. The oldest remains of red deer currently known on this island are the carved antler pins, one of the most common items found within the Carrowmore chambers.

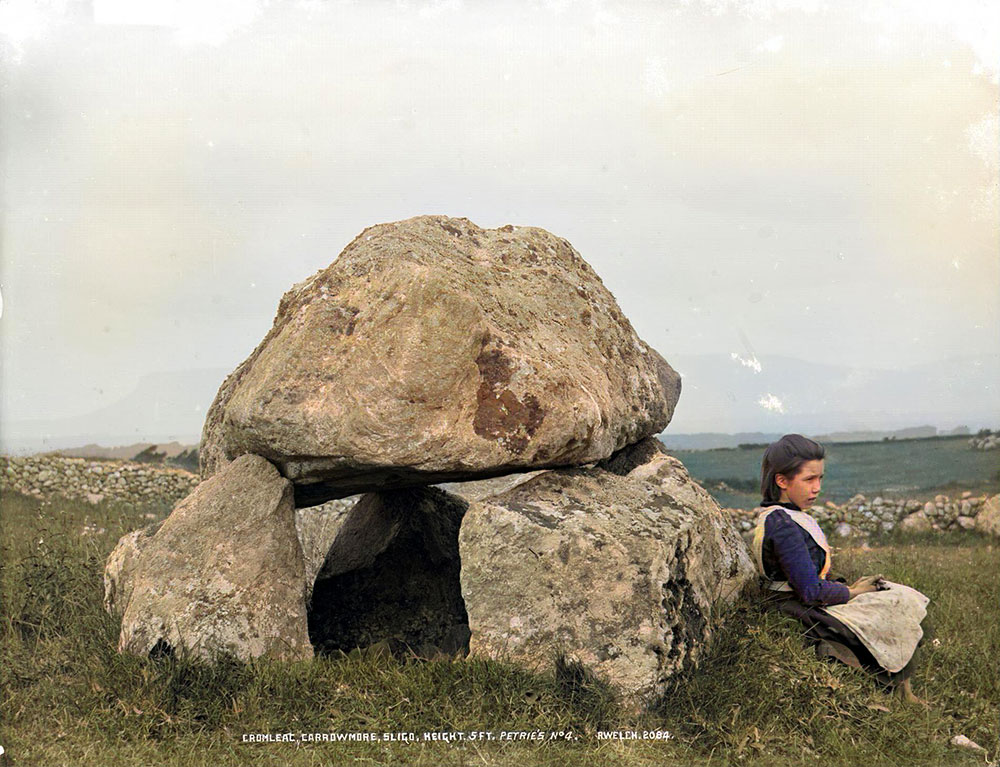

Because so many of the monuments have been destroyed and disturned, the remaining records of some circles are the comments by George Petrie from 1837, an essay by Charles Elcock written in 1883, the excavations by Wood-Martin and the illustrations of William Wakeman from the 1880's are extremely valuable. A series of amazing photographs of the Carrowmore monuments were taken by Robert Welch in 1896 and William A. Green in 1910.

Superb aerial footage of the monuments at Carrowmore and Knocknarea.

Office of Public Works

Carrowmore is managed by the Office of Public Works, a government body responsible for the care of national monuments. A small visitor centre, which is subject to an entry fee, carpark and public toilets give access to about fourteen of the remaining monuments. Guided tours are provided daily and the site is open seasonally. The site opened on March 15th and will remain open until September 2nd when the visitor centre will colse for renovations. It is possible to book a tour by contacting the Visitor Centre at this link.