Dowth South

The large entrance kerbstone K1, above, marks the entrance to the chamber of Dowth South. Although this entrance stone has fallen forwards, an engraved spiral and some cupmarks can be seen carved into it. There is no public access to this chamber in general, and permission from the Office of Public Works is required to visit. However, over recent years it has sometimes been opened for the winter solstice sunset, when visitors who have gathered for the sunrise at Newgrange can come to Dowth to witness the corresponding sunset.

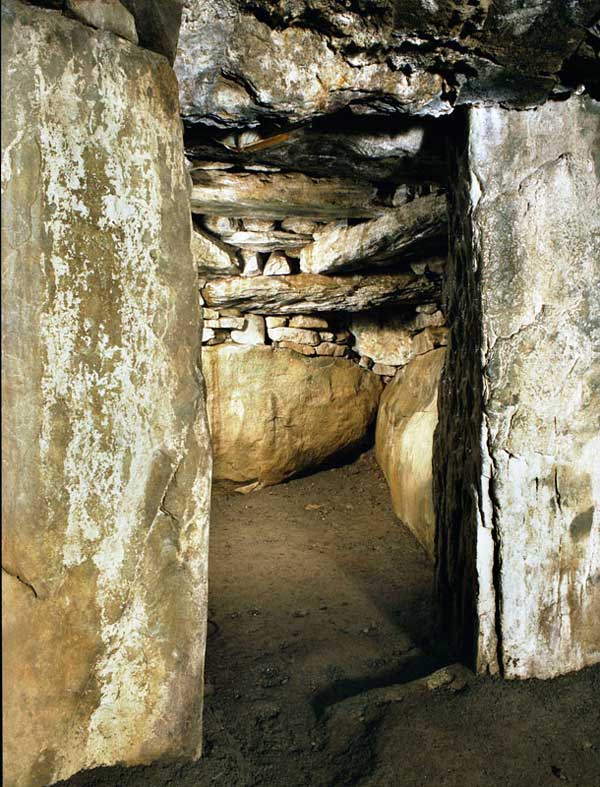

The passage is four meters long and constructed with three large orthostats on each side. The passage opens into an unusual round chamber, about five meters in diameter, with a sill-stone dividing the passage from the chamber. There are twelve orthostats (structural stones) which form the roughly circular chamber, and an empty space where there may have been a thirteenth stone.

The chamber was originaly roofed with a massive corbelled beehive vault which had collapsed in antiquity, or possibly was damaged during Firth's excavations at Dowth in 1847. George Coffey stated that the chamber had no roof in the 1880's. A concrete roof was added around 1885 or 1886 during renovations on Boyne Valley monuments supervised by Sir Thomas Newton Deane. However, this modern ceiling does a poor job of keeping the chamber dry, and the interior can be very muddy, and the chamber stones are often wet.

Deane claimed to have discovered Dowth South also but, as has been shown, this was not the case. In his plan of the tomb, made before its restoration, he shows only two orthostats at each side of the passage, whereas three are now present. The front one at each side of the entrance at present is only about half the height of the others and perhaps these two were not noticed until later, or they may have been out of position and been replaced during the conservation work. In the course of that work, a concrete roof was placed over the chamber.

The Tumulus of Dowth, County Meath,

Michael J. O'Kelly and Claire O'Kelly, 1983

Picture © Office of Public Works.

The Recess

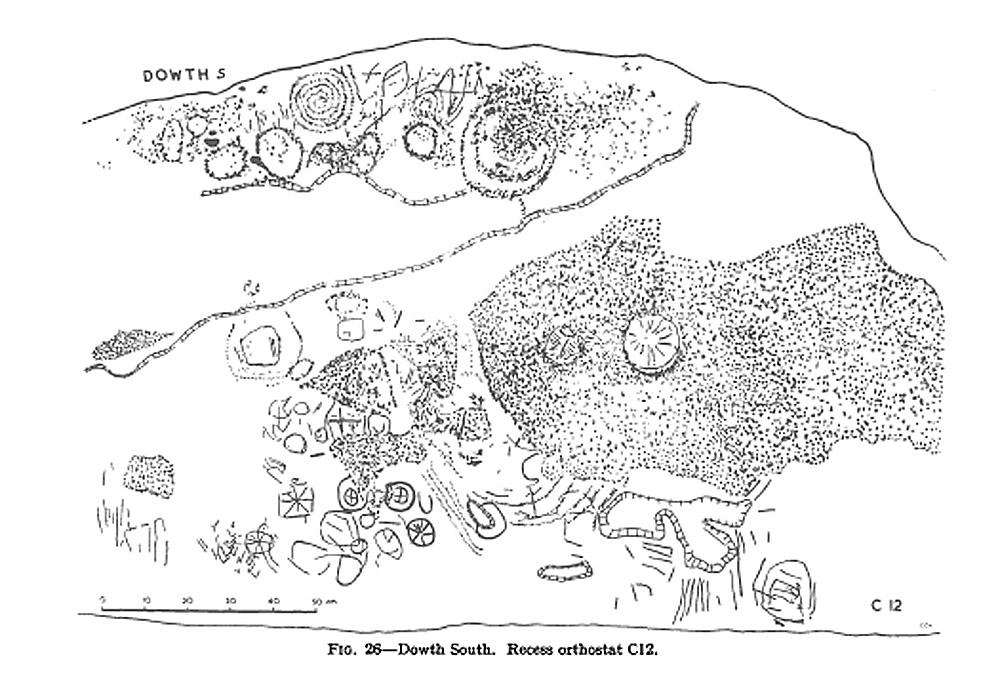

This circular chamber has quite an unusual plan when compared to other Irish megalithic monuments: there is only one recess, formed from three massive slabs on the south or right-hand side of the chamber. Another sill-stone divides the recess from the chamber. The construction of this recess is on a monumental scale, with some of the stones almost three meters long. The roof is constructed using massive corbeling, and seems to have been repaired during the 1890's renovations, when spall stones were inserted under the slabs.

The recess is at the right-hand side of the chamber and is wedge-shaped on plan, widening towards the back. The sides are formed of three large slabs laid on their long edges, averaging 2.6 meters in length. The recess measures 2.9 meters from front to back and l.6 meters from side to side across the centre. It is about 2 meters high. The roof is of large slabs placed one on another, corbel fashion, rising from the sides of the recess. Though it has been said that the roof was intact when the tomb was entered in 1847, nevertheless a good deal of repair and rearrangement of slabs is evident. The infilling of small stones between the large corbels, for instance, is certainly not ancient. There is a sill stone across the entrance though it is deeply embedded in the floor at present.

The Tumulus of Dowth, County Meath,

Michael J. O'Kelly and Claire O'Kelly, 1983

There are several small engravings in the right-hand recess which are similar to and quite probably derived from the sun wheels and rayed circles of Loughcrew

Winter Solstice Sunset

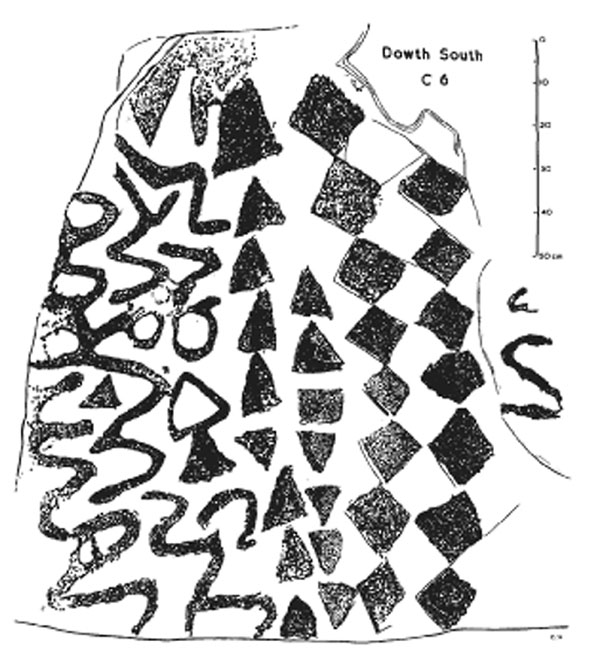

The fact that the south chamber of Dowth is oriented towards the winter solstice sunset was first noted by American researcher Martin Brennan in his book, The Stars and the Stones, published in 1984. After a series of observations made at Dowth while Brennan, who was staying at the Netterville Institure close by, revealed that the chamber had an alignment which complimented Newgrange. A broad beam of sunlight enters the passage at 4.15 pm, sweeps across the floor and illuminates the decorated stone at the back of the chamber. The stone to the left of the sunbeam, which is carved with an array of diamonds, lozanges and zig-zags, the most complex panel of art at Dowth, remains in darkness. The reflected light seeps into the right-hand recess.

Martin Brennan concluded that the monuments in the Boyne Valley were linked in an annual cycle of ritual astronomical observations. He found that the sun's rays entered several of the cairns on the winter solstice, beginning with Newgrange at dawn, Sites K, L and Z during the day, and ending in this chamber in Dowth South at sunset.

The entrance of Dowth (North) faces out towards Newgrange and the horizon beyond. Dowth acts as a synchronized counterpart of Newgrange. On the day of winter solstice the sun projects its rays into Newgrange at dawn and into Dowth at sunset. The passage and chamber at Dowth are about half the size of their Newgrange counter parts, but the projected light beam is much larger, and it remains in the chamber for a longer period of time, creating an even more dramatic spectacle. Parallels can be drawn between Dowth, and Loughcrew and Knowth, where passages are aligned to both the sunrise and sunset of a particular astronomical event. At Dowth a large circle hollowed into the entrance stone marks the position of the setting sun. The entrance stones at Dowth and Newgrange have similarities, but the Newgrange one is more formalized and clearly a later development in both technique and concept.

A second, larger passage at Dowth is also aligned to sunset. The original entrance to this passage was sealed during reconstruction. It seems to mark the cross-quarter days on 8 November and 4 February. The three gigantic mounds in the Boyne Valley, made up of hundreds of thousands of tons of material, in fact form a unified system that follows the circuit of the sun from the autumnal equinox to the spring equinox. It seems that after spring equinox interest shifts to lunar observation.

The Stars and the Stones, Martin Brennan, 1984.

The art carved at Dowth seems to be earlier than that found at Newgrange and Knowth, and the symbols are similar to the engravings found at Loughcrew, a site which certainly appears to be earlier than the three huge Boyne Valley monuments.